Dorothy Day: Not your off-the-shelf saint

The word on the "Catholic Street" is that Dorothy Day is being fast-tracked to sainthood. Pope Francis, who shows no fear of controversy, strongly indicates his admiration for her. When the pope spoke before the U.S. Congress last September, he singled out four Americans, or what he called "the Fantastic Four," for special praise: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day.

Day received papal praise for her passionate commitment to social justice and in particular her lifelong dedication to the poor and the rights of all persons... poor, oppressed and unborn. She echoes the life and loves of the pope's patron, St. Francis of Assisi.

Early in his pontificate, Pope Francis urged his priests to be shepherds "with the smell of the sheep." Day had it. Her total embrace of radical poverty and daily work with many of New York's abandoned and neglected make her a model not only for priests, but all of us who have been charged with the care of the poor.

Her unswerving dedication to the poor is surely the reason that in 2000, close to his own death, John Cardinal O'Connor of New York City began the process of Day's canonization. Deeply dedicated to helping the forgotten and left behind, Cardinal O'Connor wanted his flock and the world to encounter a truly modern saint, even a warts-and-all saint.

But as her cause picks up speed, it is setting off alarm bells, because Dorothy Day was not the Little Flower. She was no meek and mild, kiss-the-book communicant. She was a wild, undisciplined, free spirit who in her 30s began the great romance of her life. She fell in love with Christ and his Church. Before that, she lived the disordered existence of a confused bohemian.

Born in 1897 in Brooklyn into a restless, nomadic family, she moved across the country, first to San Francisco and later Chicago. The family was nominally Christian and Dorothy was baptized and had some bare bones religious instruction. In high school she proved to a good enough student to win a scholarship to the University of Illinois. Dorothy was described as a "reluctant scholar," interested more in the radical politics going on in the real world than the realm of academics. Thus, she left college after two years and moved to New York City's Lower East Side, the country's then center of radical politics.

Getting work in a series of extreme left wing newspapers and little magazines, she discovered what was to be a major part of her life long cause: the forgotten poor. Reflecting on those years, she wrote that her allegiances kept shifting back and forth between socialism and anarchism.

She, also, full-throatedly embraced the Bohemian life-style around her. Those early years of her late teens and on into her 30s were filled with one dead-end job after another, drunkenness, and a series of sexual affairs. One of her lover's got her pregnant and convinced her to make what she believed was the mistake of her life: She had an abortion.

Years later, she became pregnant again by her common-law husband. Against his wishes, she had this child. The birth of her daughter, Tamar, was the pivotal event of her life. It was her Paul-of-Tarsus moment. She found transcendence in the most earthy of things, a helpless baby. Daily caring for her daughter, Tamar, led her ona search for Tamar's creator. In turn, that search lead her to the Catholic Church, hardly a favored institution of her Bohemian friends and colleagues.

It was not the high theology of the Church that drew her, but the Church's work with New York's homeless and helpless. Here, in serving the poor and doing God's work, her worlds came together.

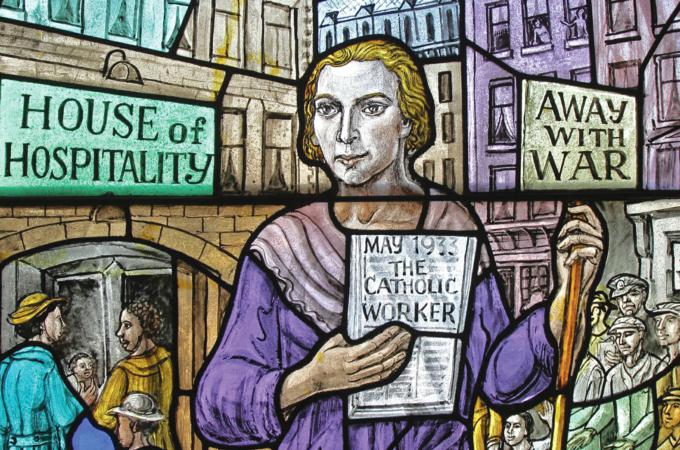

She, with her longtime associate, the mystic Paul Maurin, founded the Catholic Worker, a free newspaper that for over 80 years has been the beacon for many Catholics and Protestants, calling attention to the folly of war and the abuses of capitalism. The newspaper, indeed, lit a fire: the Catholic Worker Movement, which, like its founder, has been a passionate, and sometimes imprudent, center of the Catholic Left.

It is not only her abortion, then, that caused some to question her promotion to sainthood. It is her political stands, supporting the communists' oppression of the Church during the Spanish Civil War and supporting atheist Fidel Castro's takeover of Cuba. On the other hand, she was no advocate of pure communism or socialism. She advocated "distributism," an economic theory very much in line with Catholic social thought. Popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and favored by conservative Catholic thinkers, such as Hilaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton, distributism has been described as "a third way between socialism and capitalism."

The forthcoming process of Dorothy Day's canonization will be one of fire, not ice. One suspects she'd like it that way. She lived her Catholicism "large" and she spoke truth to power long before it became a cliché. She made big mistakes and loved big. She comforted the sick and the homeless, and she was, and is, a thorn in the conscience of the comfortable.

Our column last month was on progressive icon, Margaret Sanger. We cannot help comparing Ms. Sanger's devotion to abortion and her crusade to limit births among black Americans to the passionate commitment to life and service to the poor of her contemporary, Dorothy Day.

Two American women reflecting two rival visions of a worthy American life.

- Kevin and Marilyn Ryan, editors of "Why I'm Still a Catholic," worship at St. Lawrence Church in Brookline, Mass.