A moment of pure Christian springtime

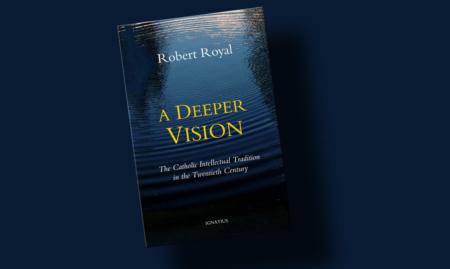

The 20th century saw a remarkable outbreak, in nearly every area of cultural and intellectual endeavor, and in many nations and traditions, of a creative exuberance among Catholics. Philosophy, literature, music, political theory, and economics, philosophy of physics, and the new medium of film, all saw brilliant contributions by thinkers and artists whose work was deeply informed by the Catholic faith. This movement has been called a "renaissance," or rebirth, because it was marked by a youthfulness and spirit of new discovery. As the movement is still so new, and not yet integrated into a Catholic's standard education, we need a guidebook for it, which Robert Royal now provides in his "A Deeper Vision: The Catholic Intellectual Tradition in the Twentieth Century" (Ignatius Press).

"Beautiful things are rare. What exceptional conditions must be presupposed for a civilization to unite, and in the same men, art and contemplation!" wrote Jacques Maritain, perhaps the leading philosopher of this renaissance, in his profoundly meditative, "Art and Scholasticism" of 1920: "Under the burden of a nature always resisting and ceaselessly falling, Christianity has spread its sap everywhere, in art and in the world; but except for the Middle Ages, and then only amid formidable difficulties and deficiencies, it has not succeeded in shaping an art and a world all its own -- and this is not surprising. Classical art produced many Christian works, and admirable ones at that. But can it be said that taken in itself this form of art has the original savor of the Christian climate? It is a form born in another land, and then transplanted." One can grasp Maritain's distinction by comparing an ancient basilica, essentially a Roman public building adapted to worship, with a Gothic cathedral, which had no purpose prior to Christian liturgy.

Maritain added the following sentences, which he could not have known would be prophetic, descriptive of the cultural effulgence which was to come: "If in the midst of the unspeakable catastrophes which the modern world invites, a moment is to come, however brief, of pure Christian springtime -- a Palm Sunday for the Church, a brief Hosanna from poor earth to the Son of David -- one may expect for these years, together with a lively intellectual and spiritual vigor, the regermination of a truly Christian art, to the delight of men and the angels. Even now this art seems to herald itself in the individual effort of certain artists and poets over the past 50 years, some of whom are to be reckoned among the greatest."

A list of names would fill paragraphs, but consider Maritain, Marcel, Gilson, and Pieper in philosophy; Guardini, Balthasar, Ratzinger and Knox in theology; Peguy, Claudel, Mauriac, Waugh, Chesterton, and Tolkien in literature; Elgar and Messaien in music; Rouault in painting; Duhem and Father Jaki in science; Ford, McCarey, Borzage, and yes even Hitchcock in film.

These Catholic creators of great works no longer saw themselves as solely developing a path already set down by the medieval Church, or solely responding to the Reformation, but rather as contriving new things which had their own appeal on their own merits. They embraced everything they found good -- new media, new forms, new paradigms. At the same time they viewed themselves as responding to distinctively contemporary issues, such as the rise of atheism, materialism, and secularization; the reality of sin as shown in the World Wars, but then the rapid forgetting of the sense of sin by the same civilization that was beset by those wars; and the distractedness and dis-integration of man as found in a rapidly developing world of technology, kept captive by his own technology, and alienated both from nature and from the simple life of human childhood.

Most of us are only vaguely familiar with this renaissance, and we will need a pathway in, and a map for getting around. Someone who read solely "The Everlasting Man" of Chesterton, "The Lord" by Guardini, and watched Poulenc's opera, "Dialogue of the Carmelites," would be doing quite well. But there is no "Summa" produced by the period, and individual works, precisely because of their concentrated genius, will not be representative. Royal's book sets a context for beginners, while in its comprehensiveness, it potentially uncovers blind spots in adepts.

One might quarrel with how Royal sets things up. The book is perhaps too top-heavy in theology, not broad enough in music, literature, and science. There are odd weak points, such as its slight treatment of Gabriel Marcel and Flannery O'Connor. It neglects entirely the question of Catholic education, so deeply related to questions of the mind and of culture.

Also, it's not clear what the meaning is of this renaissance according to Royal. When Michael Novak and I teach a course on the subject, we regard its secret origin as the hidden prayer life of St. Therese of Lisieux, the great saint of charity who presides, as a Doctor of the Church, over the developments of the 20th century. We find its culmination, not in a cultural "work," but rather in the evangelizing life of a person, namely, the great papacy of St. Pope John Paul II, himself a philosopher, theologian, poet and playwright. For us the renaissance is an extended mediation on Christ's Incarnation: it is the cultural embodiment of the "universal call to holiness." Yet admittedly these bigger questions cannot be engaged without a familiarity with the matter.

MICHAEL PAKALUK, PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY AT AVE MARIA UNIVERSITY, IS AN ORDINARIUS OF THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF ST. THOMAS.

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.